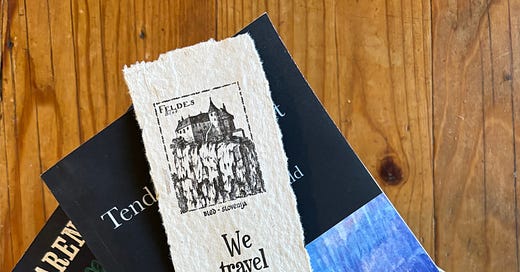

“We travel not to escape life, but for life not to escape us.” The sage philosopher Anonymous said that. I now have the quote emblazoned on a rag-paper bookmark, hand-printed on a 15th-century Gutenberg-style printing press in the gift shop of the medieval Bled Castle in Slovenia.

The sentiment rings all too true for me: When I retired from fulltime work two years ago, I vowed to travel as much as possible, as if I couldn’t see the world fast enough in whatever time remained left to me. My desire to visit new places—and revisit others—has an almost hysterical quality. I simply can’t travel far enough fast enough.

Since the beginning of 2023, I’ve visited Mexico City, New York, northern Morocco, Italy (Sicily, Puglia, and Basilicata), New Mexico, Key West, Havana, the Netherlands, Croatia, Slovenia, and Italy again (Venice). This week I’m headed to Mexico again, and in March I’ll travel to Portugal and Spain.

(Lest you think I live the life of the idle rich, let me disabuse you of that notion. Although I retired from my fulltime job, I’ve continued to work as a freelance writer in order to fund my wanderlust. Every paycheck goes directly into my beloved travel account, and every time I return from a trip I begin planning the next one. It seems too good to be true, but so far it’s working brilliantly.)

In November I returned from my latest itinerary (the aforementioned Croatia, Slovenia, and Venice) and paused to reflect on what drives me to add so many stamps to my passport. I believe the urge was programmed in me early on: when I was two, my father was sent by the Stanford Research Institute to do market research in India and our family lived in Madras (now Chennai) for a year. On our way home, we took an extended tour across Europe and my toddler brain was infused with the sensory odors of international travel: consummé broth, European bakeries, diesel fumes, and that distinctive smell that airplanes used to have. (Also, I received a fetching little certificate from TWA that verified that I had crossed the International Date Line. Where is that piece of paper now?)

It would be another 15 years before I took my next international trip but I finagled a way to work at a hotel on a Norwegian fjord for the summer of my seventeenth year. After that, my twenties and thirties were a festival of foreign travel and then, after the arrival of my two children, the fun pretty much stopped, in favor of child-friendly vacations to Disneyland and Club Med. So when I found myself retired and fully independent again, I gleefully picked up where I’d left off thirty years before.

Which brings us back to Croatia, etc. My friend Lisa and I joined a small group of fellow Americans to travel the coast of the former Yugoslavia, overnighting on a couple of islands and poking into Slovenia for a few nights before traveling on our own to Venice to see the Biennale art show.

We climbed the fortified wall of Dubrovnik, gazing out at the azure Adriatic on one side and a terraced city of red-tiled roofs on the other. We ate many variations of sea bass and squid and sardines, followed by gelato better than any I’ve ever tasted in Italy.

On the tiny island of Korčula, famed as the birthplace of Marco Polo, we wandered ancient streets and gazed at the surrounding Adriatic some more (there was much Adriatic-gazing on this trip).

On the bleached limestone island of Hvar, we visited a Benedictine monastery where the remaining nuns still make the intricate lace that has supported their order for centuries. Then we bought a picnic lunch (shrimp gazpacho, burrata and tomato salad), lay in the warm October sun, and finally jumped into the Adriatic, which was cold but still warmer than the hotel pool. (Traveler tip: because the Croatian shoreline is so rocky and home to many sea urchins, be sure to pick up a pair of water shoes before entering the water.) Last year I’d swum in the Adriatic on the Italian coast, so this felt nicely symmetrical.

Then it was on to Slovenia. We were gob-smacked by Ljubljana, which has a rich design culture and is jam-packed with Art Nouveau-style architecture. It was as if every building were donning its silliest, most fanciful hats and fabrics. Then to Lake Bled, a historic health spa town with a fairytale castle and a church on a tiny island in the lake. Our one fail was that we never managed to try the town’s legendary cream cake. (“Every town in Slovenia will tell you that their cream cake is the original, but only ours is the real thing,” said everybody.)

Finally, Lisa and I left the group and drove to Venice for four days on our own. It had been 35 years since I’d last visited the city, and there was a time—when I was a tour guide in my thirties and was taking groups of tourists to Venice every three weeks—when I felt completely jaded about the place. But that cynicism has faded with age and I’m here to tell you that Venice is as wondrous and beautiful as ever. The fact that it’s still standing, its garishly decorated palazzos still intact, is nothing short of a miracle.

One evening we attended a concert of Vivaldi’s “Four Seasons” performed by a string octet in a Baroque church. I’d tried to get out of it, reasoning that the concerti have become little more than brunch music, but Lisa was persuasive and, seeing them performed live with such amazing acoustics, the event ended up being a highlight of our trip.

Here’s another choice quote by that same philosopher, Anonymous: “Travel not to find yourself, but to remember who you’ve been all along.” Boy, isn’t that the truth. Early in our Croatia itinerary, Lisa and I befriended a couple from Pennsylvania. “Be a lion, not a squirrel,” Bruce joked to his wife one day when she was being indecisive about something. That became a credo for the rest of the trip, and it was immediately apparent to all that I was pretty consistently a lion (decisive, determined, and maybe just a teensy bit pushy). This gave me a lot to think about.

Much of my travel in my twenties and thirties was done solo; I decided where I wanted to go and I simply went. You need to be a lion to travel alone, I would argue: You must be comfortable in your own skin (or fur). You must be curious and willing to fail. You must feel okay dining alone in a nice restaurant. You must be persistent about getting to the places you want to see.

When I first arrived in Rome in 1984, where I would settle for a year, I carried a battered copy of Baedeker’s travel guide to Italy. I methodically highlighted in yellow marker every monument and church I wanted to see in the historic center (there must have been at least 200 of them), and then I made a checkmark after I’d successfully seen it. I got to every single one. (Where’s that Baedeker’s now? Probably with the International Date Line certificate.)

I like to think that, like so many of the sharp edges of my youth (not to mention my muscle tone), my leonine qualities have softened with age, and I believe they have. Somewhat. Now, instead of a list of 20 (or 200) must-see sites, I’m content with 2 or 3. I’m more easily persuaded to experience things not even on my list (like the Vivaldi concert, LISA). And sometimes I’m just happy to sit in a caffé with a coffee or gelato and watch the local world glide by.

This trip carried many other lessons, as well. One of them was our tour manager, a young Croatian woman named Ines. Like all people attracted to this challenging career choice, Ines is smart, multi-lingual, patient, resourceful, and kind. Unlike many of her professional colleagues, she’d left a three-year-old son, Maté, at home with family while she escorted our two-week tour.

“I’m here for rest and relaxation,” she’d joked on our group’s first night together, but as the days passed, it became clear that she missed Maté and her husband fiercely. She proudly showed us photos and videos and even live Facetimes with her son. She was navigating that precarious balance of career and family that so many working women face.

But Ines was balancing something else, too. As the days passed, she gradually shared her story: When Maté was just eight months old, she discovered a lump in her breast. She soon learned that she carried the BRCA gene, which gives women a 45% to 85% likelihood of having breast cancer and a 10% to 45% chance of ovarian cancer in their lifetimes.

Over the past several years, Ines had undergone 16 rounds of chemotherapy and 12 rounds of radiation. She’d had 12 of her lymph nodes removed, a radical mastectomy and an ovariectomy. She was now growing out her hair and awaiting reconstructive surgery.

And here she was, leading a group of 22 travelers who relied on her for our every question, every personal need, and every logistical requirement during our 13-day trip across two countries. At a time when most people would be licking their psychic wounds from so much stress and trauma, Ines was our spiritual leader, filling us with history, humor, and insight.

Her outlook on life was always positive and hopeful, ready to find the beauty in every new stop, despite having seen it multiple times before. She seemed to see only the best in people, even the highest-maintenance travelers in our group. And she was full of hard-won wisdom about what a gift life is every single day. In another life, perhaps Ines could have been a preacher. Her husky voice and soft Croatian accent were like music over the motorcoach’s microphone each day as we drove through tiny villages on winding roads.

On our last stop, at the island church of St. John the Baptist on Lake Bled, we studied some gruesome frescoes in the nave, including one of a woman having her breasts amputated. “That must be St. Agata,” I said, remembering that she was the patron saint of Catania, Sicily, whose church I’d visited last year.

When a Roman governor made advances on her, Agata refused to abandon her faith and chastity—as punishment, her breasts were cut off with iron shears. (Don’t worry: an archangel soon restored them.) Because of her martyrdom, Agata became the Catholic Church’s patron saint of breast diseases.

“She’s my saint!” Ines said, and I could see how happy she was to have made this new ally in her long journey back to health. No matter how many times you visit a place, it seems, there’s always something new to discover.

And, I learned, not all lions are pushy list-makers like me. Some have soft voices and gentle spirits, which belie how fierce and brave they truly are.

Hahaha! Now you've shared your food poisoning with the world! And I don't necessarily think that you're a squirrel, just because I'm a lion. I'm staying firmly neutral on that issue!

Thank you, Josh!