My friend Sharon once made an observation that I’ve never forgotten. “Your friends want you to be happy,” she said. “But not too happy.” Isn’t that so true? Your favorite colleague loses ten pounds—“Good for you!” we say. “You look so great!” But then she loses forty pounds, gets a whole new wardrobe, and exudes a daily happiness at her brand-new life. Admit it: you’re just a teensy bit envious. You don’t love her quite as much. Maybe you don’t even need to lose forty pounds yourself, but she set a big goal and she achieved it. She loves her whole life now. That’s hard to live next to.

Once upon a time, I lived a life that looked like a fairytale to everyone around me. I had a successful, handsome husband, a partner in a big law firm. I was a fulltime mom to two beautiful, smart children. And I lived in a big Mediterranean-style house surrounded by acres of vineyards, with a lap pool and a Lexus SUV in the garage. I told my friend Veronica that sometimes it felt as if people were trying to take me down a peg. “You need to understand,” she said. “You’ve got the whole package. There’s nothing wrong with your life. How many people can say that?”

For a while, that was true, and the fairytale was real. But soon enough, the package started to fray. And then the whole life fell apart. I wrote a memoir about this decade of disaster called The Ghost Marriage. And there were a few readers—people I’d never met—who felt this same sort of schadenfreude (the pleasure derived from the misfortune of another) about my previously fortunate life.

“It’s difficult to muster sympathy for a woman who had so much opportunity and enjoyed so many financial creature comforts,” wrote one reviewer on Amazon. “Most people have never lived her charmed life for even a day.” The fact that I was later brought to near-bankruptcy by my ex-husband, or that I rebuilt a new life out of sawdust and spit, made no impression on him. He couldn’t get over the fact that I had once been affluent.

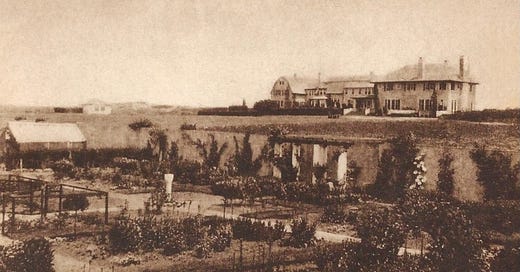

It stung in the moment, of course, but I’ve long since gotten over it. However, I was reminded more recently of this “misfortune of having too much” when a friend did an early read of my upcoming historical novel, The Ashtrays Are Full and the Glasses Are Empty. My protagonist, Sara Wiborg Murphy, was raised amid great wealth and privilege; her father was a 19th-century entrepreneur and self-made millionaire. The Wiborg family owned the largest piece of land in East Hampton, on which they built The Dunes, a 30-room waterfront mansion. Sara’s young world was filled with cotillions and lawn parties and global travel (a precursor of the lifestyle later immortalized by her friend F. Scott Fitzgerald in The Great Gatsby). She went on to become, with her husband Gerald Murphy, a doyenne of the bohemian elite in 1920s France.

But then, over the ensuing decades, Sara lost a lot: way more than the mere financial loss of my own experience. After reading the manuscript, my friend wrote, “My overall reaction was that I found the second half of the book more enjoyable—in spite of all its tragedy—than the first half. I found it harder to connect to Sara as the extremely privileged and mega-wealthy person she was as a younger woman.”

And that’s when I realized that I had picked a story that paralleled mine exactly. Again, to be clear, Sara’s wealth and tragedies dwarfed mine by comparison. But her story is one of great abundance followed by great loss, and illustrates how she decides to cope with her dramatically changed experiences, just as I tried to do. I wondered if this was what had drawn me to Sara in the first place, long before my own life followed a similar trajectory. Although she lived in a time and place that were much more rigid for women, she found ways to be creative and happy within her particular universe. I found that both moving and inspiring.

I addressed my friend’s totally legitimate concern by writing a prologue that introduces the story at the end of Sara’s life when she’s living in reduced circumstances. I wanted to let the reader know that, as much as they might resent Sara in the beginning for her eighteen-carat life, she’ll be “taken down a peg” by the end. I’m hoping that will make her character more sympathetic in those early chapters.

Here’s a little preview of that scene:

“Tuna salad on toast,” Dottie was saying. “The closest I’ll ever get to the ocean again.” She carefully removed the cellophane-frilled toothpick from half her sandwich, then the bread, then delicately placed two dill pickle slices on the salad and reassembled the whole thing. Bits of tuna fell onto the plate as she struggled to take a bite. “God damn it,” she muttered.

I’d ordered a cup of the Manhattan clam chowder. Now I tore my dinner roll and buttered just the broken piece with the smear of butter from my bread plate.

“Look at you, still the debutante,” Dottie said. “Even the way you butter your bread is approved by Emily Post.”

“To the manor born,” I smiled. “Even in the Lexington Luncheonette.”

“How the mighty have fallen,” Dottie said. “I speak not only of reputations but of arches. And pretty much everything else from the neck down.”

Here’s my advice to you: If you’re going to grow old with another person, choose someone who’ll make you laugh. At that stage, when nothing in your body really works anymore and your world has shrunk to a few city blocks, what else is there to do?

In my case, I had Dorothy Parker. In those days, Dottie and I were like soldiers in arms, keeping an eye on each other in our dotage. We were living two floors apart at the Volney Hotel, “a fine residential hotel for older women,” at East 74th Street between Madison and Fifth. Here we were, two old broads who had seen much better days. And much worse.

I was eighty-two and Dottie was seventy-two; between my short breath and her bad heart, we couldn’t go far. The Lexington Luncheonette was our favored restaurant because it was two blocks away and it served the kind of bland cuisine that didn’t wreak havoc with our ancient digestive tracts.

I looked around: the dated Venetian blinds, the marbled green vinyl upholstery. The other old diners quietly eating their lunches at eleven thirty a.m. “Such a tiny container after a life without borders,” I sighed. “Remember those long, leisurely days when we thought we’d be young forever and that nothing could ever go really wrong?”

“Well, until you were what, forty-six?” Dottie asked. “Your world was pretty damned good up until then. The ‘town and country’ life. You were raised to expect that nothing but beautiful things would come your way.”

Here’s the sweet lesson I’ve learned, both from Sara’s life and my own: Even those for whom we feel the deepest schadenfreude will eventually get taken down by one thing or another. Nobody gets out unscathed. As the comedian Robin Williams once said, “Everyone you meet is fighting a battle you know nothing about. Be kind. Always.”

Ha! Thanks for being such a loyal friend (and fan), Arthur. Such comments hurt in the moment but ultimately teach us about how our material lands with a range of readers. All good!

Kirsty, this rings so true, and really resonates with me. The emotion of schadenfreude, it seems to me, is a kind of parasite that feeds on failure — not only others’ failure, but also, in a curious way, our own. (The idea being that glorying in others’ suffering may be a kind of prophylactic against our own.) You have given me much to think about here. I can’t wait to read your novel.